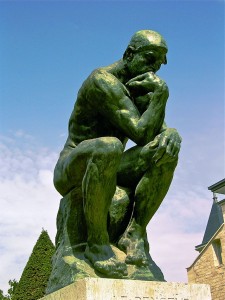

The Rational Decision-maker

In the post-enlightenment west, we have this idea that man is rational; that when he approaches a decision, he gathers the available data, calculates the costs and benefits of each alternative, and selects the one that he determines is most likely to be the best (i.e. expected utility maximization). Very few people accept this “rational actor” model as adequate, and researchers have modified it with concepts like satisficing, risk profiles, variable attitudes towards losses and gains, and findings from the psychology of manipulation to make it less mechanical and more realistic.

Moral decision-making is just a subset of universal decision-making, with the costs and benefits being measured in subjective ways. Again, we can play with the model; trying to figure out the relative weight of different virtues and how people apply them to concrete situations, but it’s still the same basic approach: a person with certain preferences and a given world-view is trying to do the best they can, given their environment and their understanding of the situation.

The Rational Advocate

But what if that gets it all wrong? What if, instead of being a decision-making organ, the conscious mind is just a post-hoc justifier, a cheerleader, a rubber stamp, a legal advocate, and a press spokesman for the real decision-maker? There is a growing preponderance of evidence that this is exactly what happens when it comes to moral decision-making: man comes to a decision pre-cognitively, then, after the decision has been made, the active and conscious mind prepares a complete dossier on why that decision “would be” the best one. One of the great findings of this literature is that the conscious mind actually believes that its post-hoc calculations led to the choice!

The problem for youth workers, teachers, and clergy is that we spend almost all of our efforts talking to the conscious advocate (what Khaneman calls the “Type Two” mind) rather than the decision-maker (what Khaneman calls the “Type One” mind). We teach our charges moral concepts and how to weight alternatives in a more Orthodox manner, but if the science is right (and I think it is), we may just end up giving them more words to justify their pre-determined decisions. For what it is worth, as a seminary professor and administrator, I take this concern seriously: we could graduate seminarians and clergy that can use Orthodox terms to justify all kinds of things, both good and wicked. Remember, the devil himself knows scripture and is a master of sophistry!

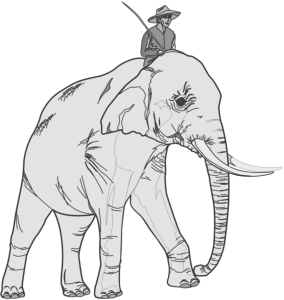

Elephants and Riders; Sheep and the Shepherd

So what should we do? Jonathan Haidt describes the situation as a rider on an elephant, with the elephant being the real decision-maker. The rider can nudge and lean, but he is far too slight to have much of an effect. If we want to get better moral decision-making, we need to work with the elephant at least as much as we work with the rider. The wonderful gift that we have as Orthodox educators and workers is that Orthodoxy has been designed by the God who knows and loves mankind and his fallen psychology; as such, we should not be surprised to learn that traditional Orthopraxis (the things Orthodox Christians are called to do) trains both the elephant and the rider. It also trains them to work together as a team in pursuit of holiness in a fallen world.

In future essays, I hope to describe how Orthodoxy modifies our psychology so that we can become truly rational sheep of the our shepherd, the source of all rationality and wisdom, the Logos Himself.

Additional Reading